“Hamlet is you, me, everyone of us”

Vissarion Belinsky

“I am Hamlet, my blood is chilled”

Alexander Blok

For two centuries the Russian intelligentsia have regarded “Hamlet” as a reflection of their own essence and historical fortunes. The changing interpretations of Shakespeare’s tragedy by Russian critics, writers, painters, composers, theatre artists, etc., mirror with extraordinary precision the evolution of Russian society and culture. To conceive the substance of any period of Russian history in the 19th and 20th centuries you should just find out how people of that time interpreted Hamlet: then you’ll touch the nerve of the moment.

For two centuries the Russian intelligentsia have regarded “Hamlet” as a reflection of their own essence and historical fortunes. The changing interpretations of Shakespeare’s tragedy by Russian critics, writers, painters, composers, theatre artists, etc., mirror with extraordinary precision the evolution of Russian society and culture. To conceive the substance of any period of Russian history in the 19th and 20th centuries you should just find out how people of that time interpreted Hamlet: then you’ll touch the nerve of the moment.

Hamlet filled the lives of Russia’s greatest theatre personalities: those who actually produced the play and those who were just meditating on it.

The theme of Hamlet, “the best of men”, “the Christ-like figure” is interwoven with Konstantin Stanislavsky’s life in art up through his last years when he worked on the play with his Studio’s young actors.

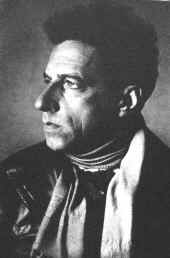

All his life Vsevolod Meyerhold was preparing to direct “Hamlet” and the more painful his life got for him, the more acute was his perception of the tragedy’s meaning. In the middle of the thirties he asked Pablo Picasso to be the set designer of his “Hamlet” production, Dmitry Shostakovitch to compose the music, and Boris Pasternak to make a new translation. The great director’s idea wasn’t and couldn’t be realised. After the closing of his theatre in 1938, Meyerhold dreamed of writing a book – at least a book! – on “Hamlet”, but even for this he had no time: he was arrested and killed.

For more than twenty years, from 1932 to 1954, “Hamlet” wasn’t performed in Moscow: quite atypical for Russian theatre history. At the same time Shakespeare was made an official cult figure in Soviet ideology. The best Moscow theatres produced “King Lear”, “Othello”, “Romeo and Juliet”, and a lot of Shakespeare’s comedies; but not “Hamlet”. The main reason was: Josef Stalin, who generally favoured the classics, hated “Hamlet” as a play and Hamlet as a character. There was something in the very human type of this Shakespearean Prince that caused “the great leader’s” scorn and suspicion. His hatred for the intelligentsia was transferred to the hero of the tragedy – with whom Russian intellectuals always tended to identify themselves.

Stalin never publicised his feelings about Hamlet – except in one case. The Party Central Committee’s famous 1946 Resolution launching a shattering attack on Sergei Eisenstein’s film “Ivan the Terrible” accused the director of turning the great Russian Tzar into “a miserable weakling comparable to Hamlet”. It is quite possibly the document was composed by Stalin himself.

Of course the ban on “Hamlet” wasn’t officially declared. The play became, silently, “non-recommendable” for the stage. The theatres had learned to catch these sorts of hints from the authorities’.

Naturally, the tragedy reappeared on the Moscow stage in 1954, immediately after Stalin’s death. In the middle of the fifties “Hamlet” was staged all across Russia. Two productions were most popular: Nickolai Okhlopkov’s at the Moscow Mayakovsky Theatre and Grigory Kozintsev’s at the Leningrad Pushkin Theatre.

In his recently published Diaries under the date October 1st 1953 (seven months following Stalin’s death), Kozintsev pointed out: “The beginning of ‘Hamlet’ rehearsals. Feel myself like a dog coming to a tasty cube of sugar. Can this really be true? May I try it at last?”

At last the ban was lifted – theatres were now permitted to “try” the Prince of Denmark. But there was a more important reason for the play’s enormous popularity at that time than just a desire to taste a forbidden fruit. “Hamlet” happened to perfectly express the main tenor of the early post-Stalinist period: a sudden recovery of vision, the collapse of illusions, and the painful revaluation of values.

Those who saw Okhlopkov’s 1954 production years after the premiere (“Hamlet” was on in the Mayakovsky Theatre’s repertoire till the middle of the next decade) might find it hard to understand the enthusiastic response to it by the first audiences. People of the sixties found the production’s style too operatic and old-fashioned. They disliked the luxurious monumentalism of Vadim Ryndin’s sets, with huge iron-wrought gates dominating the entire scenic space, the rattling lattices (Denmark is prison!) and abundant drapery.

To appreciate the real importance of Okhlopkov’s interpretation – notwithstanding all this opera! – one had to see it through the eyes of the young people of the early fifties, who recognised themselves in Hamlet portrayed as a very young person, almost a boy (the director’s conception, not the actor’s age, alas!), who suddenly discovered a bitter truth about the world.

Of note, in the fifties the mood of the first posts-Stalinist generation was expressed primarily in the stagings of “Hamlet”, and only then was it conceptualizated by modern playwrights.

An apology for intellectual doubts as opposed to the official philosophy of unquestioning political faith, and a defence of “Hamletism” in the traditional Russian sense, were the central points in Kozintsev’s theatre production – bold enough for 1954.

To avoid official criticism Kozintsev decided to finish his “Hamlet” in a most optimistic way. Fortinbras was cut; after Hamlet’s death, the hero of the tragedy suddenly rose again to recite Sonnet 74. Behind the resurrected Prince the amazed audience saw the enormous shadow of Nike, Greek goddess of victory. The idea was: Hamlet is dead, but Shakespeare’s art is immortal. Quite naive, of course, but these were just the first steps of the new era’s theatre.

However the director couldn’t foresee the authorities’ response. The Chairman of the Art Committee immediately demanded the director should present a detailed explanation why Fortinbras was cut. The reason was not special affection for the Prince of Norway. State officials just performed their duty – to guard over a classical text, to defend it from any sort of free interpretation. This time perhaps they were not too wrong.

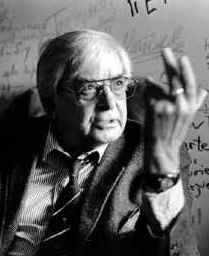

Ten years passed from Kozintsev’s “Hamlet” to his 1964 cinema version of the tragedy.

Kozintsev’s film was, and is, extremely popular in Russia as well as abroad. The film is clear, clever, intelligent, and full of good taste. First of all, the director made a flawless casting choice – he had invited Innokenti Smoktunovski to play Hamlet.

Smoktunovski performed Shakespeare’s character as if it were written by the author of The Idiot and The Brothers Karamazov. A few years before “Hamlet” the actor had played his best role in theatre – Prince Myshkin, a saint-idiot of Dostoevsky. The character of Prince Myshkin deeply influenced Smoktunovski’s Prince of Denmark. His Hamlet’s soul in Shakespeare’s interpretation was like a perfect musical instrument, which responded painfully to the slightest falseness in people and the world. The best moment in the film was the recorder scene: “Though you can fret me, you cannot play upon me”; Hamlet’s soft voice here became low and firm. This was the voice of a young intellectual who did not submit.

Smoktunovski performed Shakespeare’s character as if it were written by the author of The Idiot and The Brothers Karamazov. A few years before “Hamlet” the actor had played his best role in theatre – Prince Myshkin, a saint-idiot of Dostoevsky. The character of Prince Myshkin deeply influenced Smoktunovski’s Prince of Denmark. His Hamlet’s soul in Shakespeare’s interpretation was like a perfect musical instrument, which responded painfully to the slightest falseness in people and the world. The best moment in the film was the recorder scene: “Though you can fret me, you cannot play upon me”; Hamlet’s soft voice here became low and firm. This was the voice of a young intellectual who did not submit.

Innokenty Smoktunovski died a few years ago. He was 69. But in our memories he has remained as the young Prince Myshkin and Prince Hamlet – the parts played by him in his youth.

The youngsters of the sixties considered Grigory Kozintsev’s film (not Smoktunovski’s Hamlet) to be too academic, theatrical and sentimental – not to mention Kozintsev’s and Okhlopkov’s “Hamlets”.

New audiences, as well the new theatres, rejected the pathetic romantic style of traditional Shakespearean productions. The times gave way to more radical interpretations. All the silks, velvets and other romantic paraphernalia were gone. Shakespeare’s characters appeared on an ascetic, empty stage dressed in worn-out leather and home-woven robes. The directors of the new generation – Anatoly Efros, Yuri Lyubimov, Voldemar Panso, as well as some of their elder colleagues (first of all, Georgy Tovstonogov) – have brought with them a rough, tearless Shakespeare; they tended to see the Bard’s plays from the standpoint of Brechtian political theatre.

The Histories, previously dismissed as hard to stage, suddenly advanced to the forefront of the Shakespearean repertoire. The Histories’ contents become projected on Shakespeare’s other plays bringing about in the sixties and seventies a whole series of politicised versions of the tragedies, including productions of “Hamlet”.

Almost all that period’s Shakespearean productions – for example of “Macbeth”, “Coriolanus”, “Richard the Third”, “Hamlet”, even sometimes the comedies! – in different ways treated the same problems of human existence in the conditions of an all-powerful totalitarian state. They tended to demonstrate the ruthless and dirty machinery of a murderous political order. In particular, the final scenes were interpreted in the same Jan-Kottish manner which came to be known as ‘the rondo principle’: Richmond and Malcolm followed the footsteps of Richard and Macbeth and everything started all over again. Political history was moving in the same fate circle. It was not important whether the directors had or had not read Jan Kott – the ideas expressed both by the Polish critic and the Soviet directors were in the air of the times.

The general trends of the period were represented in the “Hamlet” directed by Voldemar Panso at Tallinn’s Kingisepp Theatre in 1965. (The theatre movement in Estonia, as well as in Russia and elsewhere in USSR, confronted the same socio-political realities and was characterised by similar artistic tendencies.)

The world in Panso’s “Hamlet” was coloured in greys and blacks; it lacked air or light. Silently tiptoeing across the stage were people in plainclothes spying on Hamlet, Ophelia, Laertes and even Polonius. Athletically built young men, dressed in black leather, marched self-confidently up and down, always ready to execute any order from anybody on the throne. The court of Claudius was reminiscent of a military staff – the military-bureaucratic machinery functioned faultlessly, turning human beings into unthinking components of “the System”. Neither Guilderstern nor Rosencrantz were born traitors and spies. But the System, step by step, turned them into such – for they had once said “yes” to it.

The part of King Claudius was played by Yuri Yarvet, who some years later starred in Kozintsev’s film “King Lear”. Claudius’ fate was at the logical centre of the production – maybe a little more than Hamlet’s. The King found himself the most unfortunate human being on earth. He wasn’t born a killer. It was not out of lust for power that this small, weak man had spilled his brother’s blood. Being merely part of the System, a detail of the Grand Mechanism, had made him desperate. He craved for freedom, and hoped to obtain it by ascending to the throne.

Now that the crown was his, Claudius felt bitterly deceived, for nothing had changed. He was still a marionette of the System, a powerless component of the political machine, just a more important one. This stoop-shouldered king, his feet hardly touching the steps beneath the throne, presented a miserable figure. His wrinkled face expressed nothing except suffering and fear. He had fear for everyone, especially of Hamlet.

Hamlet knew only too well how the System worked. He knew that by pressing a button he could set the machine into motion. When in the final scene the Prince exclaimed: “O villany! Ho! Let the door be lock’d: Treachery! seek it out”, the thugs in black leather immediately blocked off the entrance. They had got an order – that was enough for them. One of the lads grabbed Claudius from behind, so that Hamlet’s sword easily stroked the defenceless king.

Hamlet in Panso’s production was nothing but an innocent youth. He had no illusions or hopes. He knew a lot and that knowledge was burdensome. He knew that political success could be swift and easy. All he had to do was to “press a button”. But he also knew that touching this button would stain his hands and he preferred not to.

In the end the young Norwegian towered above the bodies, holding the crown which had fallen from the head of the dead king. The cherished dream of Fortinbras had come true, but he didn’t feel any joy. He looked as grievous as Claudius did in the beginning. Fortinbras started his ascent at the point where Claudius had just fallen. The wheel of history had gone full circle. Nothing had really changed.

With years, however, “the rondo principle”, once praised as a revelation, degraded into a platitude and fell victim to aesthetic inflation. The politicised, “Brechtian” interpretations of Shakespeare began to reveal their limitations. The theatre people’s heightened interest in political issues, the passionate preoccupation with structure and functioning of an authoritarian state, gradually gave way to a tendency of the theatre to interpret the collisions of classical drama in broader philosophic terms: man and fate, man and universe, man and death. Yuri Lyubimov’s famous 1971 production of “Hamlet” at Moscow Taganka Theatre is a good case in point.

Taganka’s “Hamlet” appeared at one of the gloomiest moments in post-Stalinist history (Soviet tanks in Prague, dissidents in prisons, the KGB in full power, etc.). Paradoxically, however, it was a time of the real flowering of Russian theatre. The stage was fed with the energy of opposition to the regime – not necessarily expressed in the forms of straightforward political theatre.

Shakespeare productions now reflected society’s prevalence of tragic sensibilities. In 1970 Anatoly Efros produced “Romeo and Juliet” at the Moscow “Malaya Bronnaya Theatre”. The production was permeated with despair and pain that would have befitted “Hamlet”. Renaissance Verona appeared as a grim world dominated by crude force and leaving no place for hopes.

Shakespeare’s lovers were stripped of their traditional sweetness. They looked like mature people, drawn together not only by love but also by a desire to resist the absolute power of loutishness. They knew they were doomed to die: as a critic said, those Romeo and Juliet must have read “Hamlet”.

The Shakespearean productions by Efros and Lyubimov were then perceived as a spiritual challenge to dreadful times, as a lesson of courage and staunchness in insuperable circumstances.

The stage imagery of Taganka’s “Hamlet” was marked by a famous symbolic curtain. The critics (including myself) wrote the word with a capital letter: the Curtain. Moving across the stage in all directions, it presented an ambiguous symbol of the supernatural forces of death and tragic destiny. In some scenes the lighting made the curtain look like a gigantic spider’s web where the people, “flies to the gods”, were caught. Or it transformed into a wall of earth, or become an avid monster chasing its victims. The Curtain filled up the entire universe of the scene and nobody could escape it.

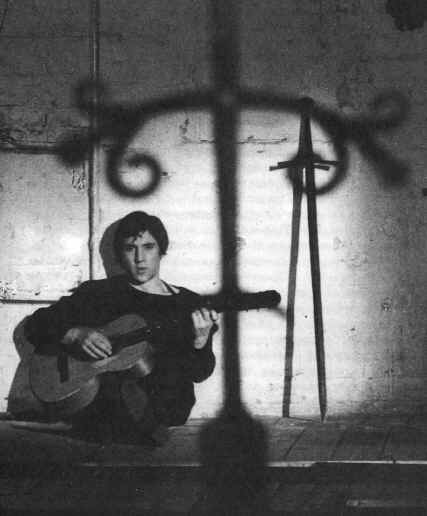

Hamlet, played by Vladimir Vysotsky, was every inch a Russian. Nothing about him suggested self-admiring abstract speculativeness or intellectual arrogance. The ways of the world aroused in him not a philosopher’s melancholic reflection but real suffering, almost physical pain, which was breaking his heart. He had “lost his mirth” long, long ago. There was little new the Ghost could reveal to him.

Vysotsky’s Hamlet implicitly expressed the attitude of the generation that had experienced the rise and fall of the sixties’ social hopes, and was faced with the question of what could be done. The idea of the world as a prison was self-evident for this Hamlet. What did matter was finding ways of coping with the time that was “out of joint”.

There were no logical motivations for the resistance to the invincible forces of the tragic universe represented by the Curtain. But this wrathful Hamlet, in open-neck sweater, speaking, whispering, crying in a coarse, “scorched” voice, was led by the righteousness of his impatience, by the blasts of his saintly hatred. He had thrown himself into the rebellion against the whole world, against the Curtain. Hamlet’s desperate struggle was like burning himself alive. In this battle the reward was not hope but saving dignity.

Vladimir Vysotsky was an actor, a poet and a singer, one of the most popular figures in unofficial Russian culture of the sixties and seventies, enormously loved by the people of all generations and classes and hated by the authorities. He died at the highest point of his career at age 41. Vysotsky’s funeral in 1980 become an unofficial national event, a mournful, silent protestation of thousands and thousands people in the Moscow streets. He was buried in Hamlet’s costume.

Playing in the Taganka production, Vysotsky composed a poem about the Prince of Denmark. His idea of Hamlet was not significantly identical to Lyubimov’s concept. On stage there was no questioning of the rightness of Hamlet’s rebellion. As a poet, Vysotsky was more apprehensive of the moral threat inherent in the hero’s struggle. A rebel is required to be killed. The rebellious Hamlet is required to communicate with the world of Claudius in the latter’s native language of bloodshed.

The days have smelted me into unstable alloy,

Which revels out, hardly having frozen,

And goes to pieces.

I’ve spilled the blood like everybody else.

Like everybody else I wanted my revenge.

My rising before death became my downfall.

Ophelia, I don’t accept the rottenness,

But having killed, I’ve made myself an equal

To him, with whom I share the grave.

(literal translation)

These lines in Vysotsky’s poem anticipated the range of problems that were raised in some of the more recent productions of “Hamlet” in Russia.

It has become common in the Russian tradition to treat Hamlet as an alter ego of the author and to perceive the world of the play through the eyes of the Prince of Denmark. However the next period in the stage history of the play brought with it attempts to transport this attitude into a question. The directors of “Hamlet” started to doubt the ethical lawfulness of Hamlet’s cause; they proved with enthusiasm: in his endeavours to set right the time that was “out of joint” Hamlet had to resort to violence – at least five deaths are on his conscience. That may be a commonplace for a Shakespeare scholar, but for the theatre this could be a sort of revelation. Behind this approach, new for the Russian stage, there was a mood of impotence and passionate self-accusation notably intensified in the minds of the intelligentsia in the later years of the Brezhnev era.

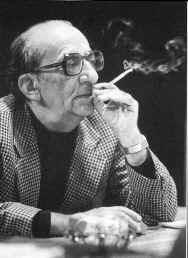

Andrey Tarkovsky’s 1977 production of “Hamlet” at the Lenin Komsomol Theatre in Moscow was the only theatrical work done by the great film-director in his home-country.

This production, with all its drawbacks and imperfections (theatrical language wasn’t native Tarkovsky), had conveyed an idea substantially religious in its meaning.

Tarkovsky treated “Hamlet” as a story of the destructive impact which violence produced upon the human soul. He saw Hamlet’s guilt in his readiness to be a judge of human lives. The director’s concept was to reject the judgement – even a correct one – that ended with blood. The last scene of Shakespeare’s tragedy was followed by a dumb epilogue: in semi-darkness Hamlet slowly arose from his death-bed and raised all the victims (not only his) – Gertrude, Laertes, Claudius. He called them out from non-existence, and carefully led them along the stage as if silently asking their forgiveness. The Christian moral subtext of this episode, as well as of the whole Tarkovsky production, was evident to everybody (one should remember the official Soviet position to any expression of religion in art).

In 1986 at the same Lenin Komsomol Theatre another film-maker, Gleb Panfilov, extended polemics to Russian theatre and critical tradition to idealise the Prince of Denmark, “the best of men”, that time, not connected to religion and in a much more radical way.

Shakespeare’s play in Panfilov’s production served no more than as an occasion to pass a sentence upon the director’s own generation – the people who were children during the war, reached maturity in the sixties, the time of the most radiant social hopes, and who, in the later years came to disillusionment and disintegration.

Representing that generation are Hamlet, Horatio, Guildenstern, Rosencrantz, Ophelia, and Claudius, a new young king, too. Age-mates and former friends, they betrayed themselves and sold each other out. Hamlet got himself involved into a battle for power, and from the outset was transformed into the same kind of murderer as his school-mate Claudius. Hamlet, in Panfilov’s production, killed in cold blood. He knew no doubts. Any mention of self-reproach were cut from Hamlet’s monologues. His conscience was not agitated; he experienced no moral pain.

This sort of person was bound to be followed by barbarians. And they came. Led by Fortinbras, they marched with semi-bent legs to the rhythm of hard rock. Horatio, the only survivor, joined this squad of primates, trying to pick up the rhythm.

No doubt, Panfilov was less interested in Shakespeare’s text than in the anxieties of his generation and deserved all the critical arrows (including my own) that were shot at him after opening night. But, however excessive the radicalism of his interpretation may have been, this expressive, energetic production, abounding in a vital force, helped bring out a distinctive and extremely important trait of the country’s social reality.

In a sense all stage history of “Hamlet” in Russia, from the first post-Stalinist years till the end of Soviet era, could be seen as a changing portrait of the generation that entered into Russian history as “the people of the sixties” and passed through very different periods, including a new rise – a very short one – in Gorbachev’s time.

In the most unfavourable social circumstances (maybe partly because of them) the people of the sixties created a really great theatre, a series of excellent Shakespearean productions. The energy of resistance accumulated by the theatre could be converted into genuine artistic values, not only political ones. The Taganka “Hamlet” or, let’s say, Anatoly Efros’ “Othello”, were first of all outstanding works of art, pieces of an amazing theatre.

Russian theatre has a rich experience of surviving under totalitarian power. The problem now is whether the theatre will be able to maintain its significance as the most important instrument of national self-consciousness and self-expression in conditions of political freedom. Whether Russians will be able in the future to make great new “Hamlets” without saying: “I am Hamlet. My blood is chilled”.

|

|

|

By Alexey Bartoshevich

Источник: Газета "English"